Thirty years ago, between the two rounds of presidential elections, a group of gendarmes were taken hostage in a cave on the island of Ouvéa. On the 5th of May 1988, an assault was launched. Operation Victor resulted in the deaths of nineteen Kanak militants and two French military personnel. In the lead up to the referendum for independence in New Caledonia to be held in November, we look back and give voice to the testimonies of those who witnessed these tragic events that bought peace and unity to New Caledonia.

From the 22nd of April 1988, twenty-two gendarmes were kept hostage in a cave in Gossanah, in the north of the island of Ouvéa. In response to the FLNKS order for an ‘active boycott’ of the presidential elections, young militant independentists lead by Alphonse Dianou, had decided to occupy the police station at Fayaoué. The operation turned sour, four gendarmes were killed and twenty seven others were captured and taken hostage.

Eleven of them were taken south to Mouli and released three days later. The remaining sixteen were held in the north in the Watetö cave, close to the independentist stronghold of Gossanah. Four days later on the 26th of April, the cave was discovered by Special Forces chief negotiator Captain Philippe Legorjus. An initial negotiation failed and Captain Legorjus along with six other Special Forces soldiers, a magistrate and a prosecutor surrendered and became captive. The island was surrounded by the French military, journalists were forbidden, and Ouvéa became cut off from the world.

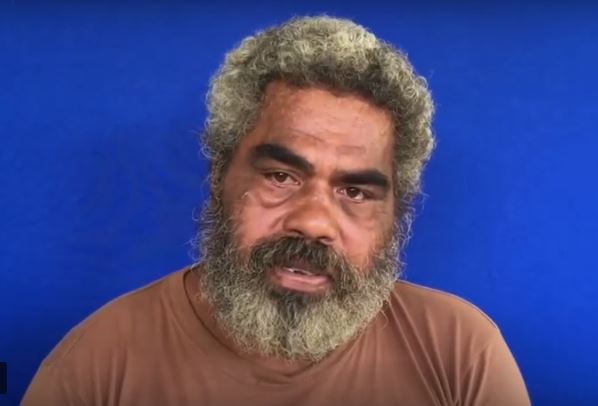

Alain Benson, Lieutenant-colonel of Police

The rapid and successful negotiations carried out by the police in the south were little indication of what could be expected in the north. “We were faced with militants who were more resolute, more determined”, remembers Lieutenant Colonel Alain Benson, Chief of the territorial police of New Caledonia in 1988. “We had difficulty finding the cave and understanding exactly what was happening. Nobody spoke, there was a blanket of silence over Gossanah. Despite the pressure we put on the tribe before the military arrived, we had no idea where the captives were. People mocked us and we became nervous”.

“I think we disturbed the tranquillity and customary order of the village”, reflects Lieutenant Colonel Benson. “To our great surprise and at the request of Paris, the military took control of the operations. I think that’s what had shocked the village. It surely explains why some villagers were targeted and traumatised. Gossanah lost her innocence that day”.

“I do challenge these accusations that circulated about torture and mistreatment and more”

Numerous inhabitants of Gossanah attest to having been subject to violent questioning by the forces of order. But the Lieutentant Colonel contests, “Yes, we brutally intervened in village life, but I do challenge these accusations that circulated about torture and mistreatment and more”.

“There were maybe some people who were tied up to poles in order to calm and restrain them for a moment, those who had their homes searched, but to my knowledge we never committed any acts of gross misconduct. I was on the ground the whole time, I never left Gossanah”.

Maletha Touet, Gossanah mother

Following the disappearance of the hostages, helicopters, trucks, the military and police descended upon the village of Gossanah, home to the majority of the hostage takers. Maletha Touet remembers the day when life in Gossanah changed forever.

“It was the 22nd of April after the attack on the police station. I got up early in the morning to have breakfast with the children. I was on the edge of my seat not knowing what was happening. Then in the afternoon, we saw the trucks with the hostages on board. We could see them from the side of the road as they drove past and continued into the forest. In the evening, the trucks were driven into the village then abandoned”, recounts Maletha, who then decided to gather up all of the women. “We left all the youngest children in the care of an elder and then decided to head to the field opposite the church to help the helicopters land”, she says. “The next day, I ventured to the clearing near the cave because we were asked to ensure there was no immediate danger for the police. When I came back to the village, it was swarming with soldiers”.

“Houses were destroyed and some were burned to the ground”

For several days, the women and children were locked in the school. Despite the heat, hundreds were contained in rooms with the corners being used as toilets. They were released and the police progressively retreated from the village on the 26th of April, the day the whereabouts of the hostages was discovered. Humiliated, they returned to find the village in tatters. “Houses were destroyed and some were burned to the ground”, recounts Maletha, a testimony shared among many others. They were forced to live with a neighbouring tribe for a year and half afterwards. Sacks of rice were slashed open, cars were smashed, and even chickens killed. Daily life in Gossanah was destroyed.

Paulo Wea, Gossanah villager

Paulo Wea was 23 years old in 1988. His work consisted of tending to the crops and processing coconuts at the oil factory. “We heard on the radio that there had been deaths at the police station. We didn’t expect anyone to show up here afterwards”, he says. “We were an independentist tribe so naturally the police and military concluded that the hostages would be found here. It was like a war zone. I had the impression that every single soldier in New Caledonia was here in the village. We were lead behind the church and tied to wooden posts with our legs crossed, unable to touch the ground. They demanded to know where the hostages were and who the leader was. I responded ‘I don’t know’ and a soldier jumped and kicked our thighs. We could no longer feel our legs”. Thirty years after the events, Paulo remembers the details well. “We were then made to lie on the ground and take our clothes off. We refused but we were beaten and stripped. We were naked , laid out on the ground and all I could see was dust. One soldier took his gun and fired between my legs. I thought they were going to kill us”.

Jeno Wea, Tea Porter

In April 1988, Jeno Wea was 50 years old. He fished, tended to crops, and worked at the coconut processing factory. After the arrival of the hostages in the cave near Gossanah, Jeno Wea became one of the ‘Tea Porters’. These were often young men who provided food and supplies for the cave. “We would carry mostly tea. When the situation was calm between the hostages and their captors, we would bring hot meals and roast pork”, says Jeno. We were compassionate. The village mobilised to make sure that everybody was well fed”.

Despite the tension, the logistics of the operation were well coordinated. “We divided into groups”, Jeno details. “Some of us would fish and cook, others would carry the tea to the cave, and another group would make sure the route to the cave was secure”. As a tea porter, Jeno would follow a trail through the forest, taking almost an hour to arrive at his destination. On his arrival he would always offer a customary gesture. On the day of the assault, Jeno arrived at the cave at 6am. His customary gesture was being received as a helicopter thundered above the dense vegetation. Operation Victor had begun. The sound of the rotors resonated from the rock walls of the cave entrance. Then the door of the helicopter opened and heavy machine fire rained from overhead.

“Even at my age, I can never forget what I’ve seen”

“They started to fire at us from above”, remembers Jeno, “Vince (Wenceslas Lavelloi) told us to shelter against the walls inside. We stayed inside. We didn’t see how the others had been killed, we only heard the gunfire. We could hear the cries of Muen, a young man from Wakatr. He was crying for his mother before he had died”.

Jeno came out of the cave alive and well once the assault was over. While sitting on a rock, he heard gunshots. “That’s when they executed Vince” he affirms. “These events can never be erased from my memory. I will take them to my grave. Even at my age, I can never forget what I’ve seen”.

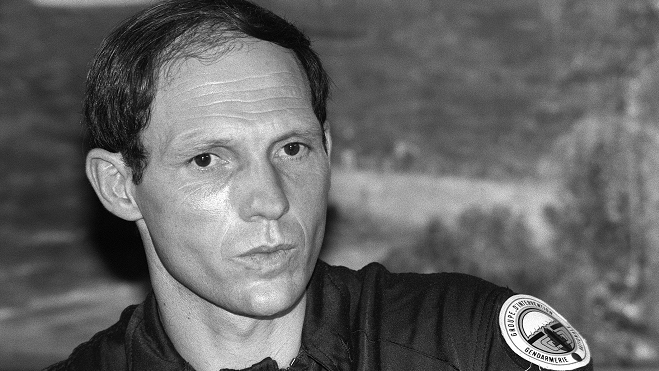

Philippe Legorjus, Captain of the Elite Special Forces

On the 27th of April 1988, fifteen gendarmes were still being held captive in the cave near Gossanah. The cave had been located and the area was secured by an elite Special Forces unit lead by Captain Philippe Legorjus. “We were waiting for sunrise so we could move in and identify the best positions from which approach the situation”, remembers Captain Legorjus. “We also had to wait for the prosecutor, Jean Bianconi, because any intervention still had to comply with legal framework. On his arrival, Jean expressed his desire to begin negotiations with the hostage takers, and stormed into the forest on a small trail”, says the Captain. “During the night, we had come under fire from the direction Jean was heading, so I instinctively followed him in to protect him. I went voluntarily. And then, the inevitable happened”.

Both men were taken hostage. Captain Legorjus would spend the whole day in the cave before being conditionally released the next day in order to negotiate a solution to the standoff. “At the beginning it was extremely intense. Everybody in the cave was very anxious. No one had slept during the night and the hostage takers knew that they were surrounded by the Special Forces”, remembers the former Captain. “The initial negotiations concerned the cave’s basic needs, everybody needed to be fed and have something to drink”.

Tensions inside the cave would rise during the night as gunshots rang out in the distance. “We understood that the majority of the hostage takers originated from the tribe in Gossanah”, continues the Captain. “The hostage takers thought that the army was ‘leveling the account’ with their families”. Captain Legorjus took advantage of the situation and convinced the leader, Alphonse Dianou, to once again release him in order to go and see what was happening in Gossanah. “I promised him that I would return the following morning, and then I left the cave”, he explains.

“Every decision made by the authorities after the initial hostage taking were contrary to what should have been done”

“I immediately thought of implementing my plan for negotiations, but clearly the government’s position at the time imposed a huge obstruction to a peaceful resolution”, says Legorjus. “Every decision made by the authorities after the initial hostage taking were contrary to what should have been done. We needed to research and put in place an informed plan to carry out a peaceful and comprehensive resolution. Sadly, in light of the tragic outcome, it could’ve been achieved “.

Benoît Tangopi, hostage taker

Benoît Tangopi experienced this assault from the other side, as a hostage taker. On the 5th of May as he was receiving the customary offering from the tea porter, Jeno Wea, a helicopter could be heard from above. Benoît was expecting the arrival of a media unit from Channel 2 France. “The helicopter hovered above us and then left. Next, two Puma military helicopters appeared”, Benoît recounts. “Alphonse cried, ‘get to your positions!’ The two helicopters commenced firing. Because I came to welcome the tea porters, I had left my rifle and belt at my post. I ran to the side of the cave to get them”.

At the same time, a land assault was about to commence. Special Forces, parachutists and commando soldiers had the cave surrounded. Hundreds of shots were exchanged as the Kanak militants fired from positions around the cave. “I was there to defend myself too“, Benoît justifies. “I had a rifle. I saw the flamethrower and heard its crackle. It was war” . The operation unfolded over two assaults, lasting a total of six hours. “I wasn’t scared, we didn’t feel fear”, he admits. “We had set out to pursue a clear objective, it was for our country”.

An attempt to negotiate was occurred between the two assaults. “They were talking to Alphonse but Alphonse refused to negotiate. He cried out ‘We will die here! You came 22,000 kilometres to get here but us, we are going to die here on our land !’”

Once the operation had finished, the scene was shocking. A complete bloodbath. Nineteen Kanaks, one of whom was a mere tea porter, and two soldiers were dead. According to the autopsies, a number of the hostage takers were found to be executed by a bullet to the back of the head. According to Benoît, Wenceslas Lavelloi was one of those executed. “They even played games with him. They paused to take photos of him, already beaten and injured. Then they took him away and we heard the gunshot. Then the soldiers reappeared while demanding who was to be next. It was the prosecutor, Jean Bianconi, who screamed ‘that’s enough, there are already too many dead!’” confirms Benoît. “That’s when we knew that we were going to survive”.

“Everything was put in place to make sure no one could be held accountable”

A judicial inquiry was opened concerning the operation and the resulting allegations, but it was quickly suspended due to an amnesty agreement as part of the Matignon Peace accords. “1988 is still here, it’s like yesterday for me”, Benoît says with tears in his eyes. “I feel terrible, each day is difficult because there was no resolution. Nobody can be accountable. I know that I did something wrong and I need to be judged and forgiven. Once that happens, my heart can rest. But everything was put in place to make sure no one could be held accountable”.

The Aftermath

In the weeks following the 5th of May, politics began to hamper investigations. Controversy swelled around the outcome of Operation Victor: Nineteen independentists and two soldiers dead. Two investigations were opened, one judicial and one military. On the 13th of May, the minister of defence, Jean-Pierre Chevènement, ordered the internal command inquiry that lasted 15 days. When he was confronted by the press on the 30th of May, the minister refuted the accusations of summary executions but admitted that Alphonse Dianou died as a result of questionable acts. These acts were severely addressed, however they did not affect the honour of the military.

Paris-Match published the famous photo on the 27th of May. Alphonse Dianou can be seen alive on the stretcher along with the other survivors. The men were imprisoned in Paris until their release in November 1988 following the law of amnesty.

Meanwhile, the judicial inquiry called into question the military’s alleged actions of voluntary homicide, voluntary assault, and failure to aid a person in danger. The inquiry focused on the deaths of the three independantists that occurred after the liberation of the hostages; Alphonse Dianou, Wenceslas Lavelloi, and Amossa Waïna, a tea porter. Around this time, France’s Le Monde published the testimony of a soldier who accused the Special Forces of having fired a shot into Alphonse’s leg while he was laying surrendered on the ground. However, the amnesty rendered all allegations obsolete.

Story produced by Laura Philippon / Steeven Gnipate and sourced from:

https://la1ere.francetvinfo.fr/assaut-grotte-ouvea-nouvelle-caledonie-grand-format-582367.html

https://la1ere.francetvinfo.fr/obseques-polemique-apres-assaut-grotte-ouvea-585309.html

Images credited to: AFP/Remy Moyen, Angela Boucko, LP.

Translated and edited by Michael Brunott